“THE ROCK”

Preface

I have always been drawn to places where beauty and discomfort collide. My photography leans toward minimalism and quiet storytelling, revealing the emotion in spaces most people walk past without noticing. I am fascinated by how light transforms the mood of a scene. A cold room becomes softer with a single glow of warmth. A harsh structure gains depth through shadow.

Mount Eden Prison is a small part of New Zealand history carved into stone. Lives layered into walls. A place built for punishment yet filled with traces of humanity. Photographing it wasn’t just documenting decay. It was exploring how a space once meant to break people can still hold fragments of their strength, fear, hope, and identity.

These images reflect what I saw and felt during rare access to a forgotten stronghold. This is how the lens translated the silence.

A Little History

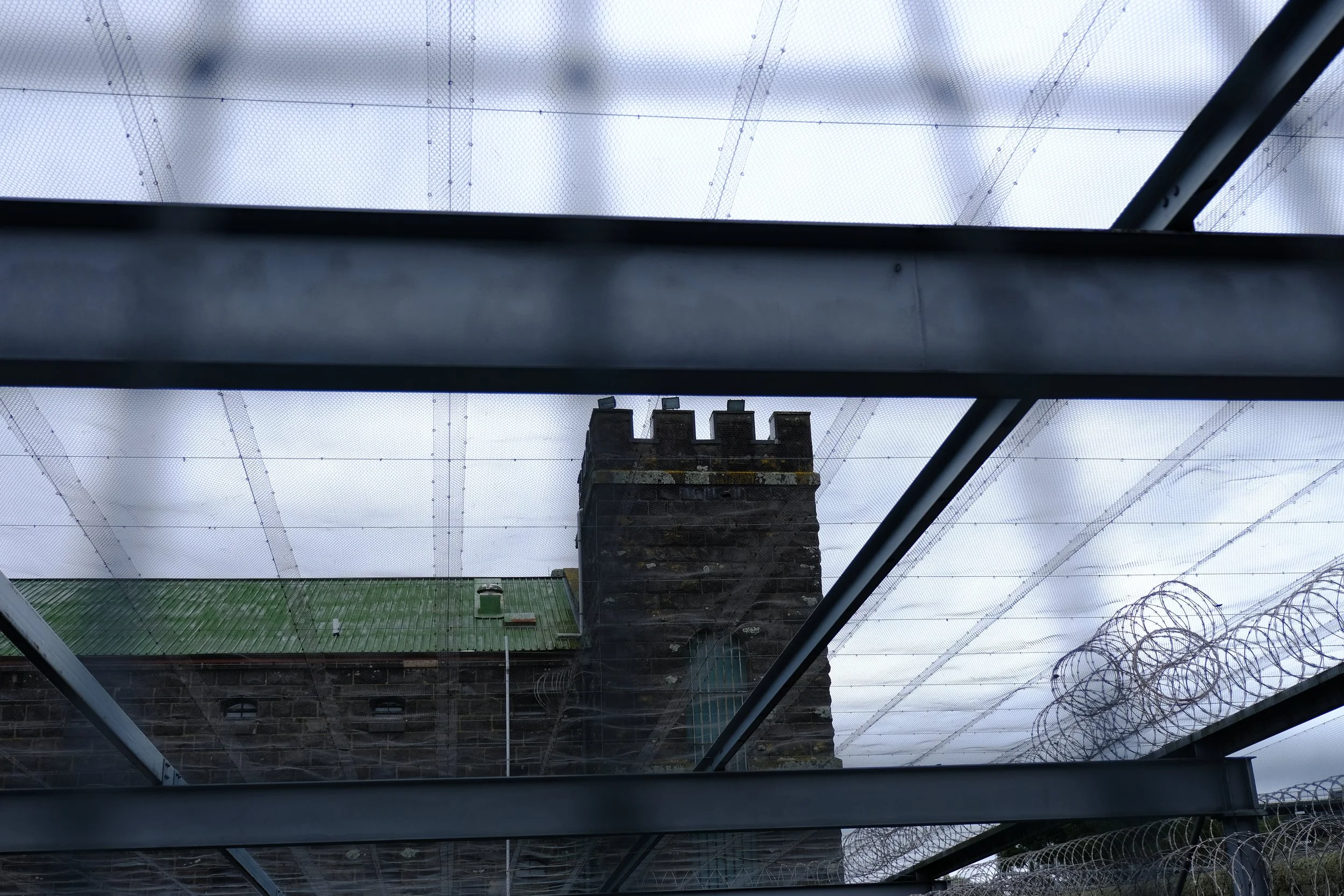

Mount Eden Prison began as a military stockade in 1856 before becoming Auckland’s main prison in 1865. The massive basalt walls were completed in 1872, and the central structure was finished in 1917. Architect Pierre Finch Martineau Burrows modelled the design on Dartmoor Prison in England, with wings branching from a central hub inspired by the panopticon principle of control through observation.

Dark chapters stain its legacy. Executions took place on-site, including New Zealand’s last in 1957 when Walter James Bolton was hanged for the poisoning of his wife. Escapes were rare, though George Wilder’s 1963 breakout became folklore. He remained on the run for 172 days, travelling thousands of kilometres and committing dozens of crimes along the way. A major riot in July 1965 raged for 33 hours, ending only after the SAS, Army Gunners, Corrections staff, and Police regained control. Today, the structure is heritage-listed as a Category I historic place. Yet behind that status sits a building that many would prefer to forget.

How It Came About

A newspaper article first sparked my interest, describing why the old prison could not be repurposed despite its heritage value. The blend of history, myth, and the emotional weight of the place drew me in. Through a few well-placed phone calls, I learned that Corrections had organised a tour for TVNZ. I requested to attend as a freelance photographer for an international agency.

During that daytime visit, a guard offhandedly said that even walking past the entrance after dark gave him chills. That stuck in my head. Curiosity won. I asked for a night visit. Then another. Miraculously, both requests were approved.

Accessing an abandoned prison built into the grounds of a maximum-security facility is almost unheard ofI I was extremely grateful for the opportunity .

The Prison

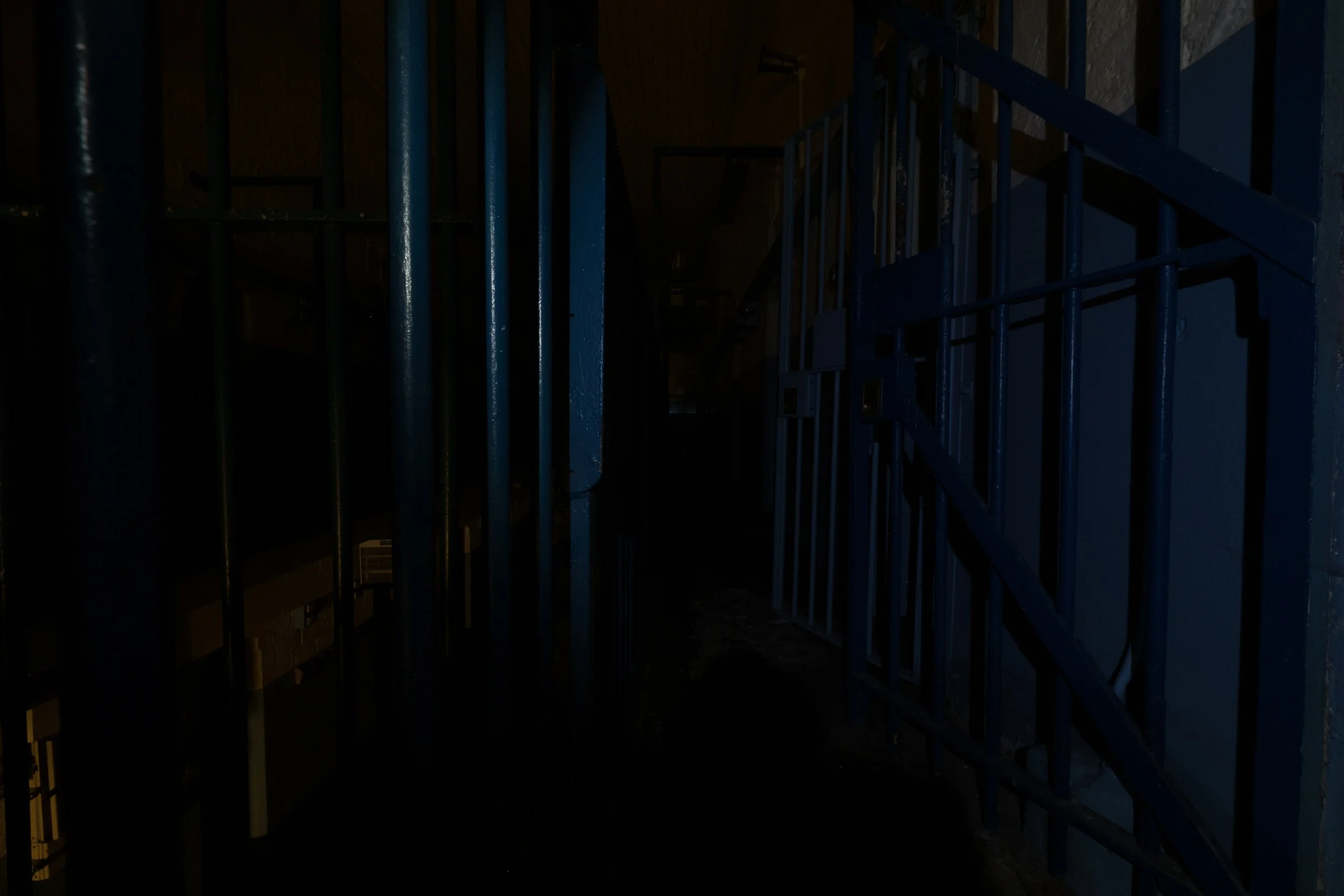

The main entrance into the old prison grounds.

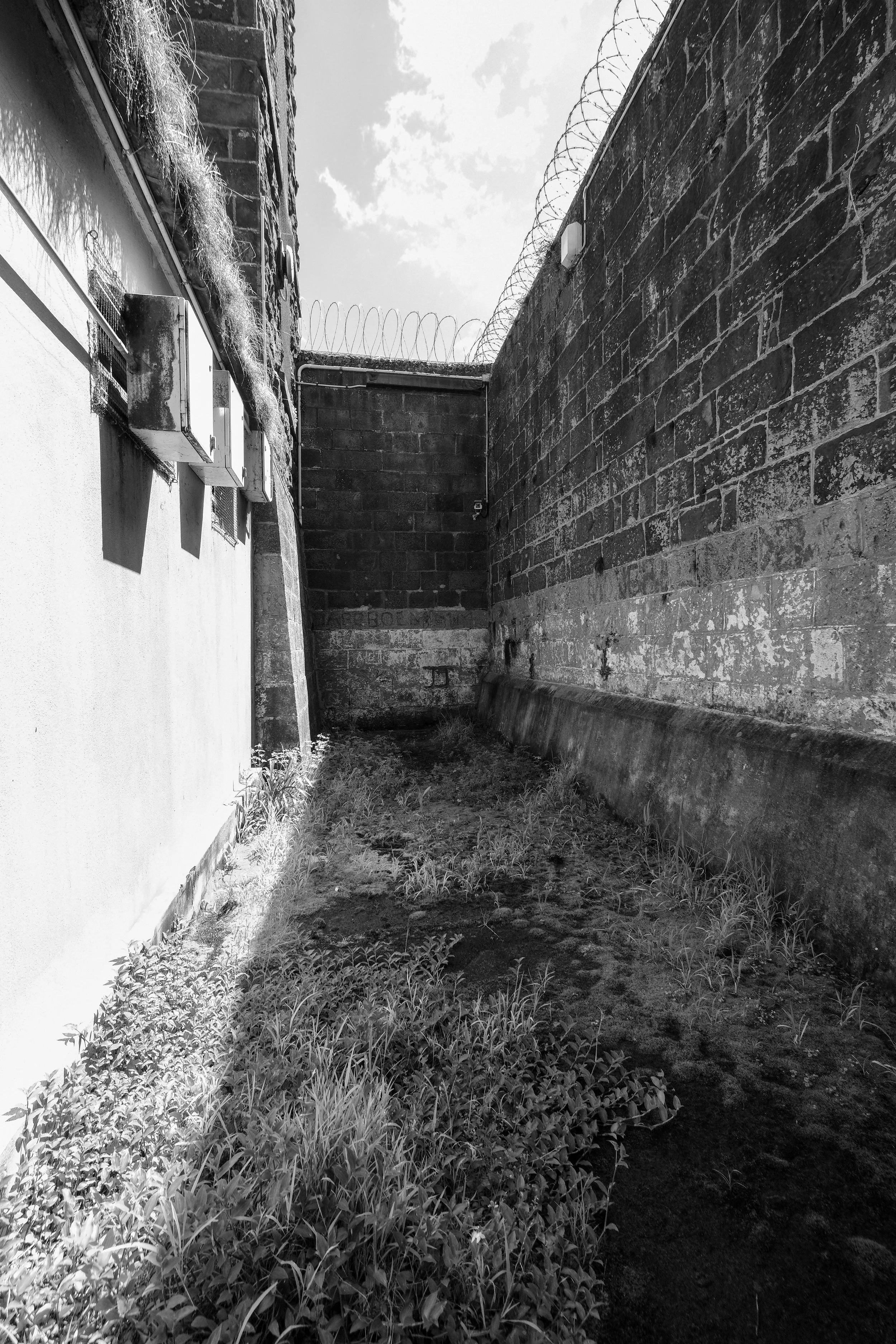

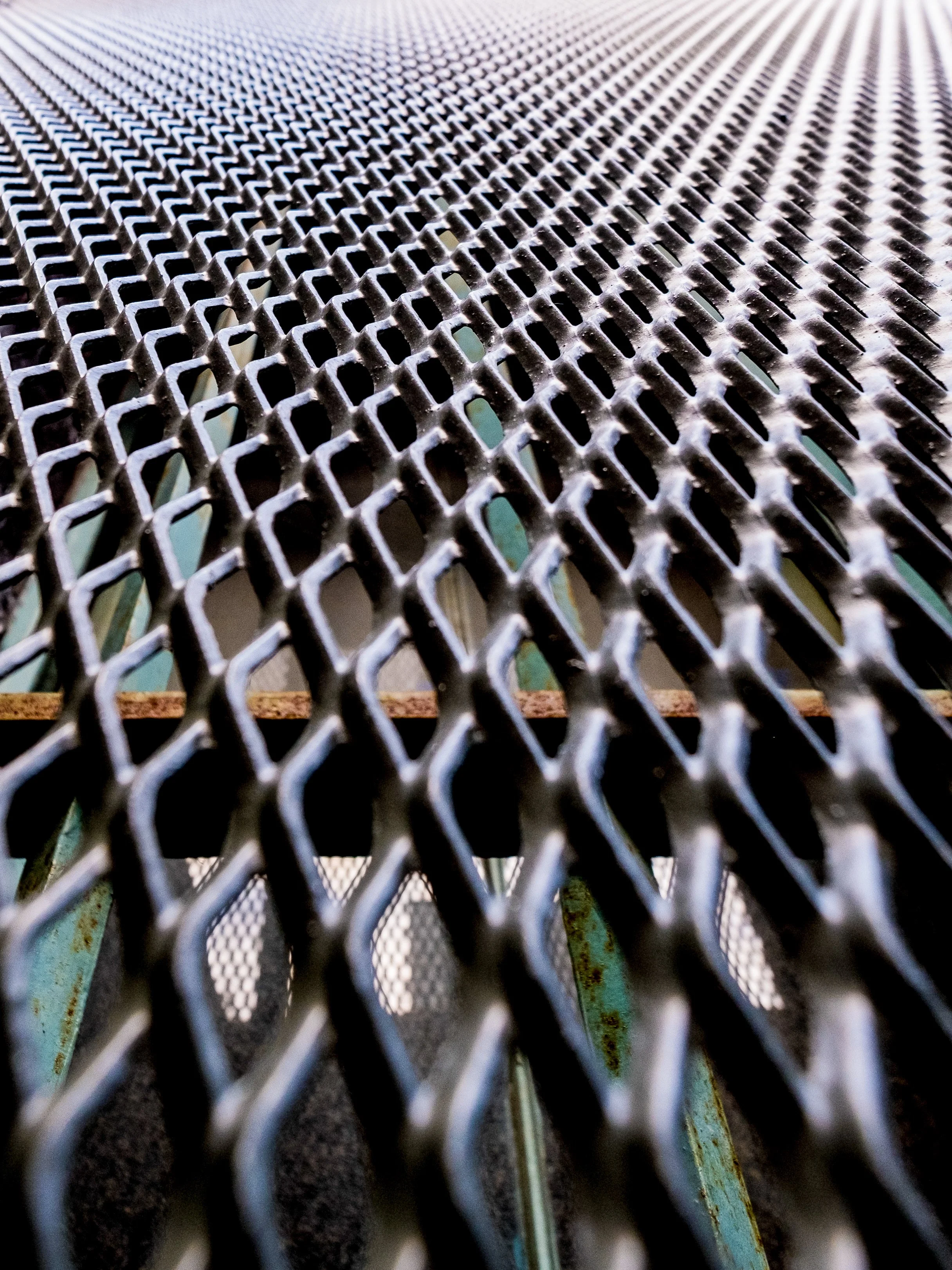

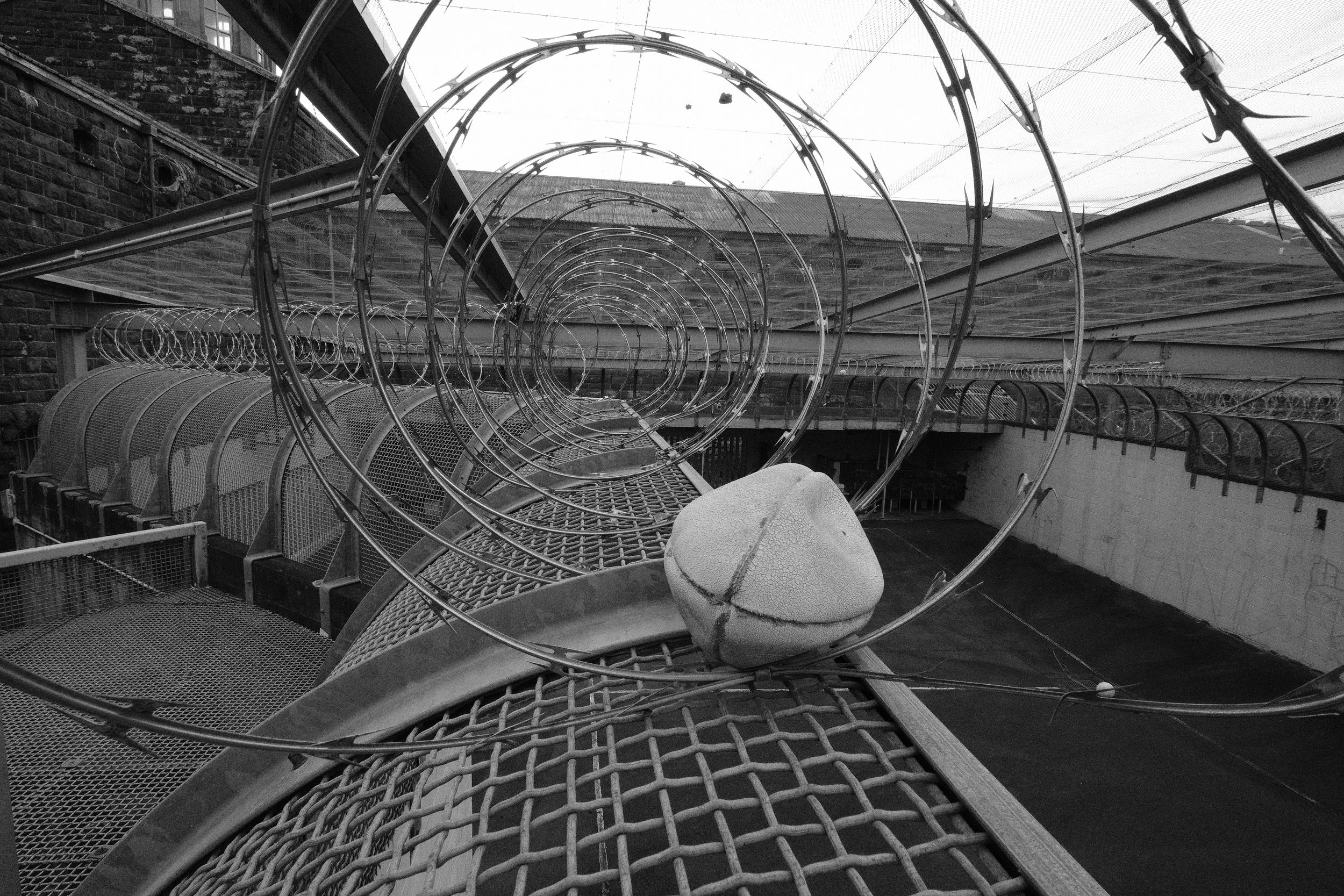

Every entry involved airport-style security: X-ray scanners, physical checks, and handing over a detailed list of every item down to my memory cards in my cameras. Two guards escorted me to the old gates, where the looming stone façade seemed part medieval fortress, part urban ruin. Weeds threaded through cracks in the rock, softening the fortress-like presence.

A tree outside happened to be covered in pink blossoms. It felt strangely out of place beside razor wire, stone walls and steel fencing, like nature was trying to dress up the brutality.

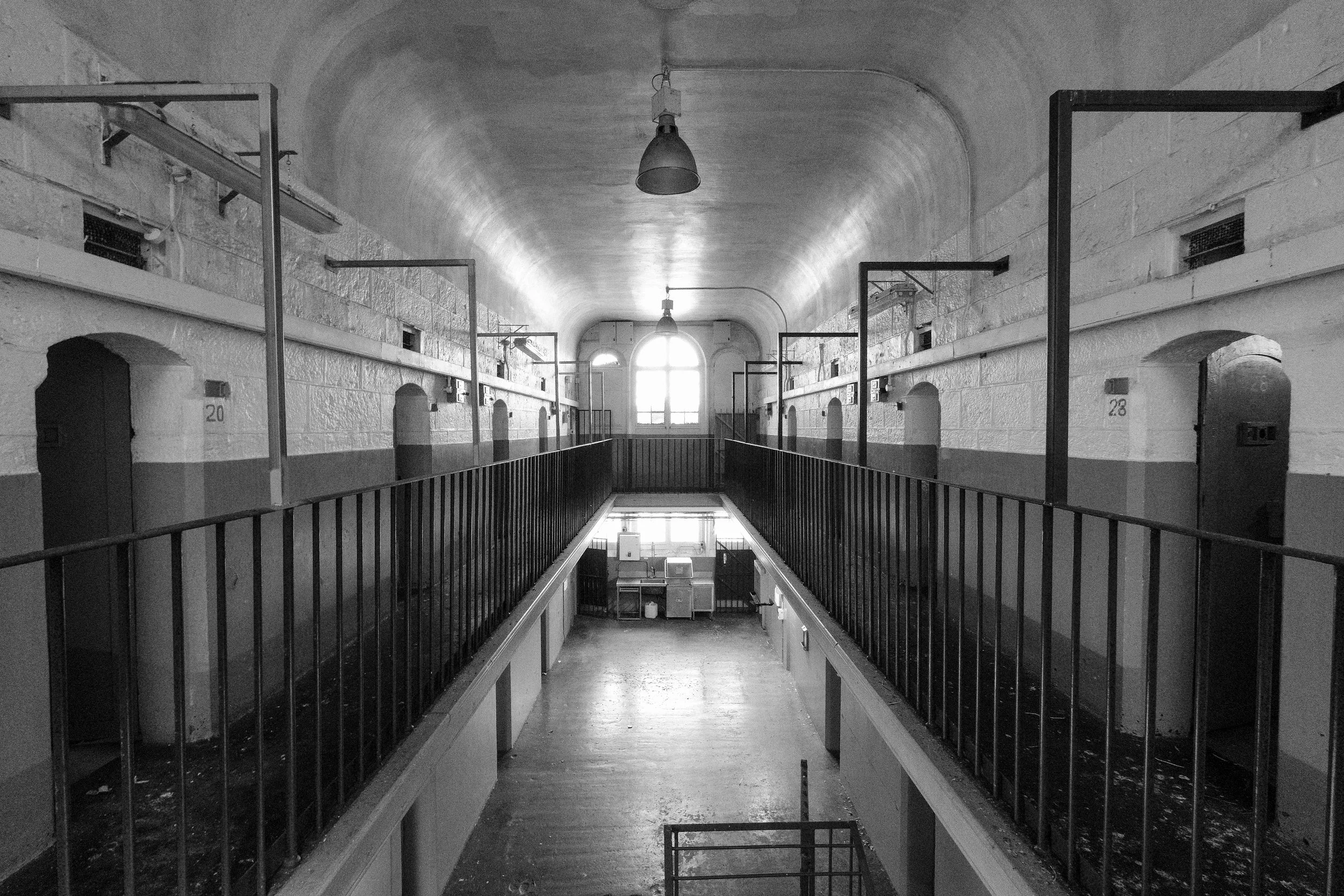

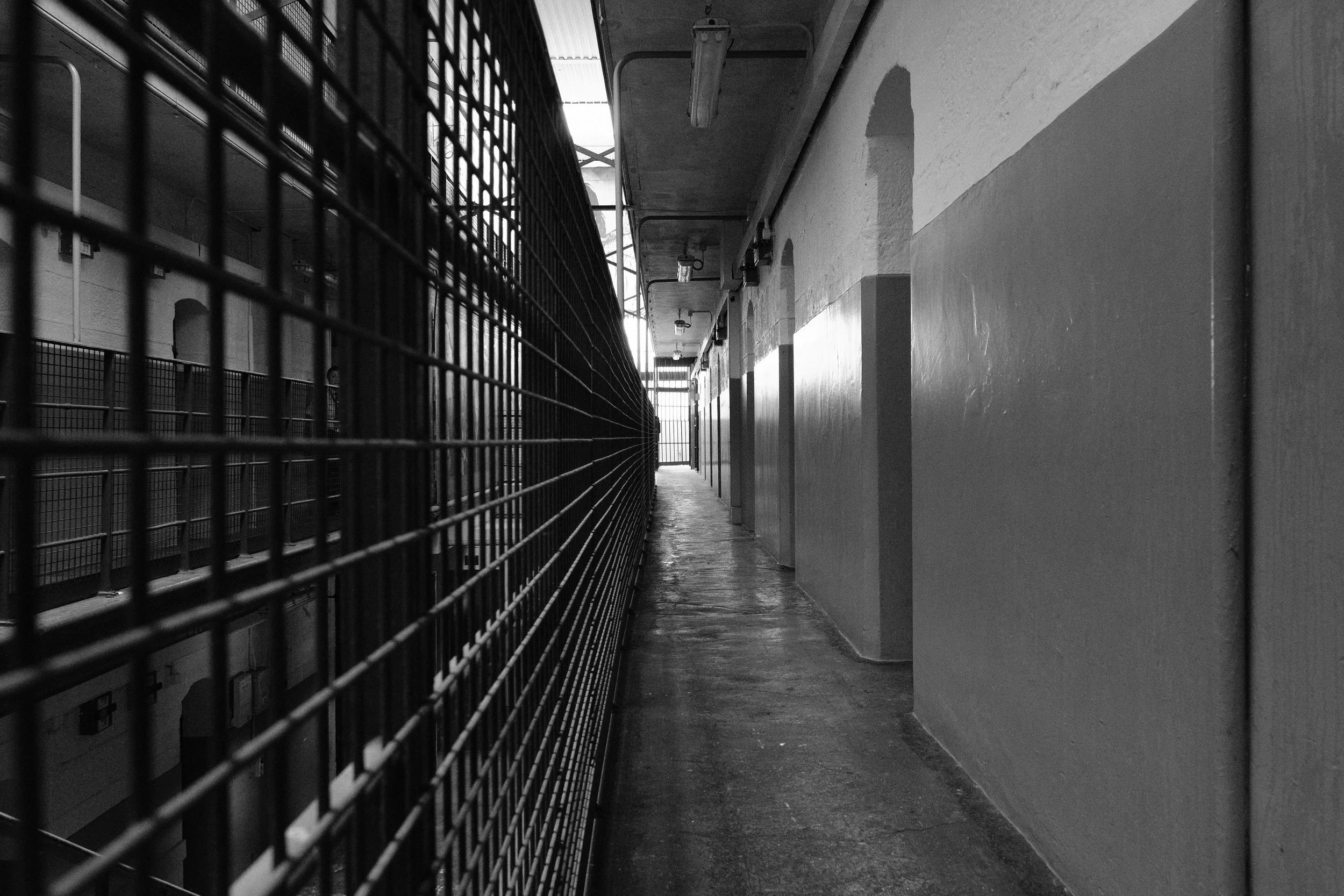

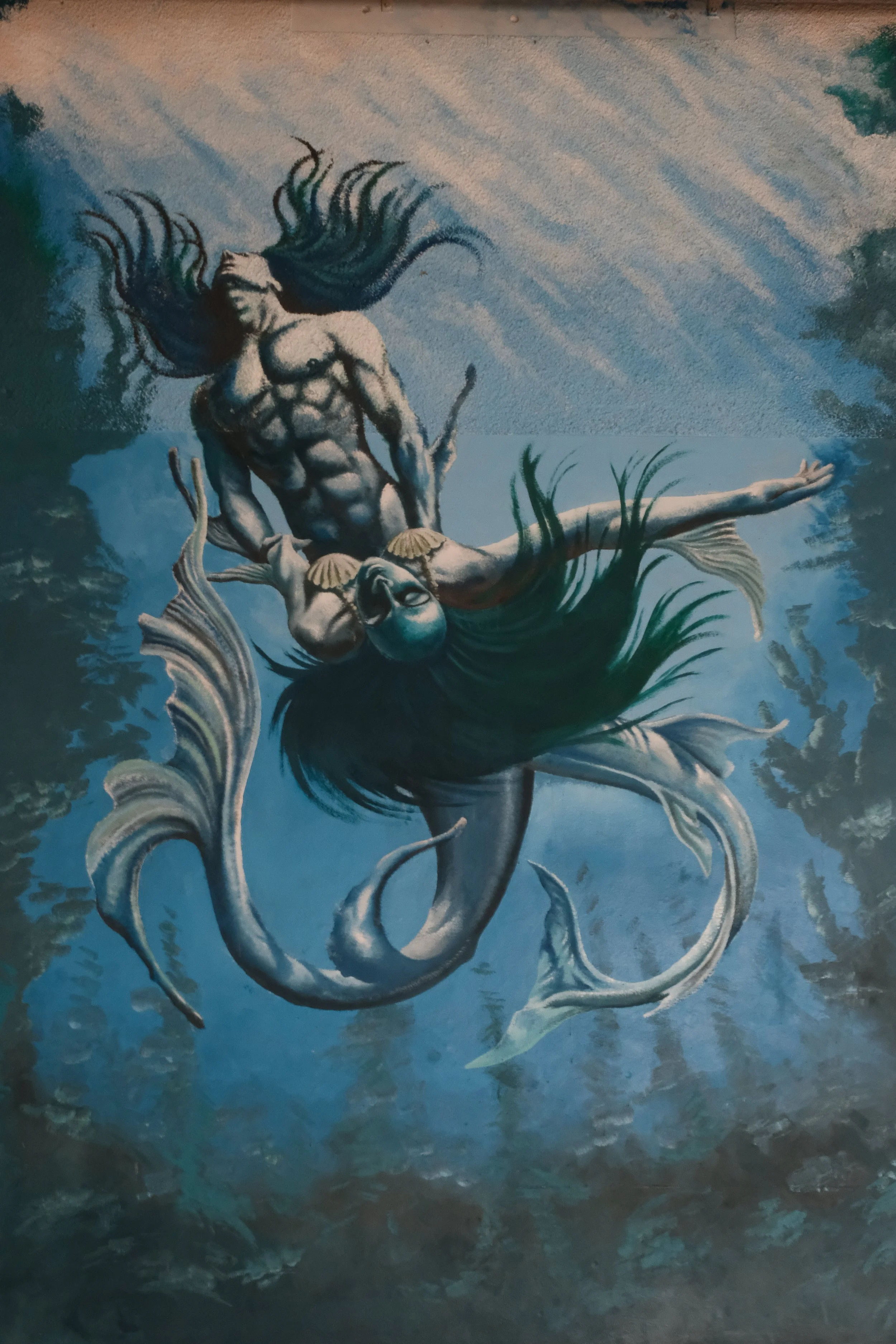

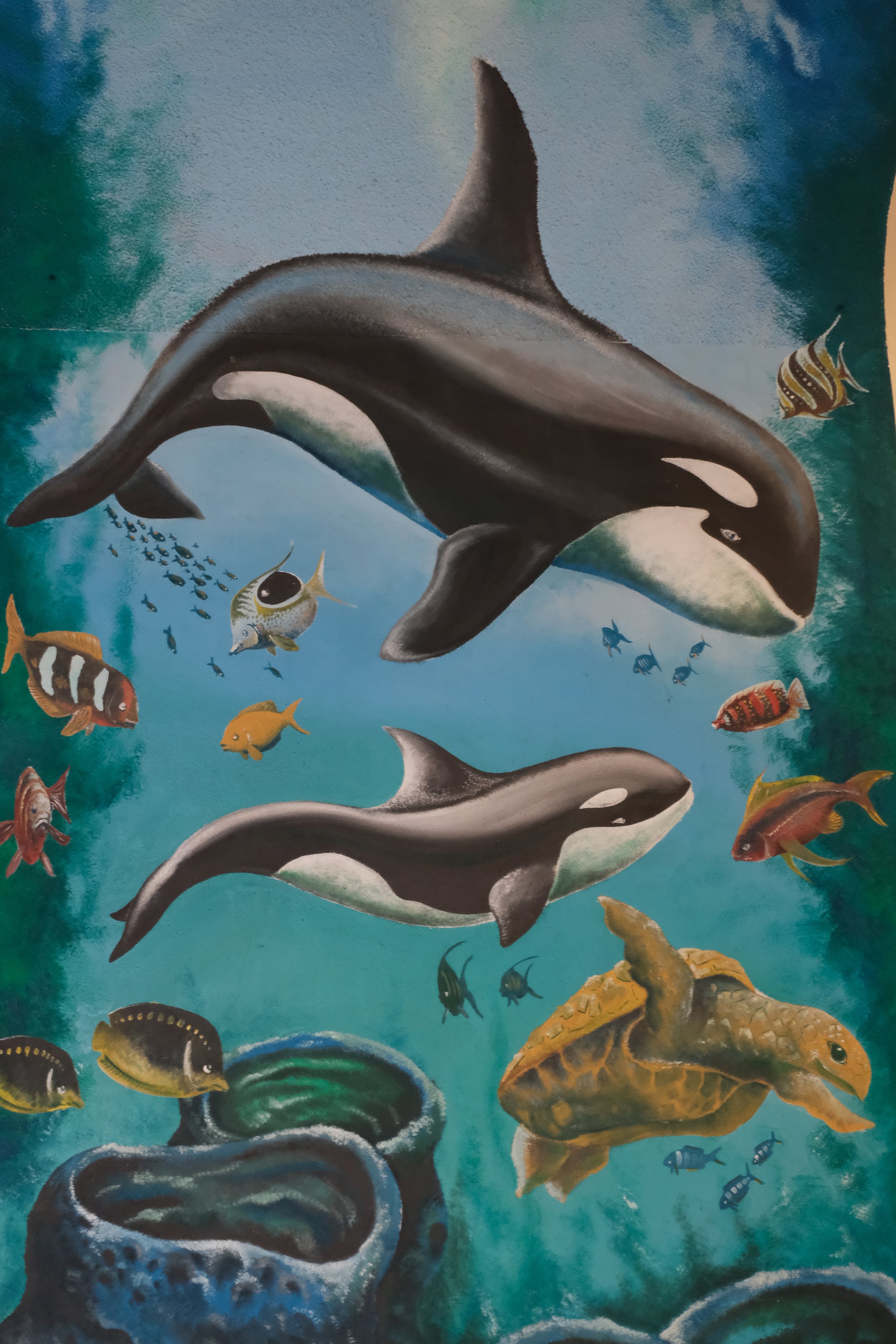

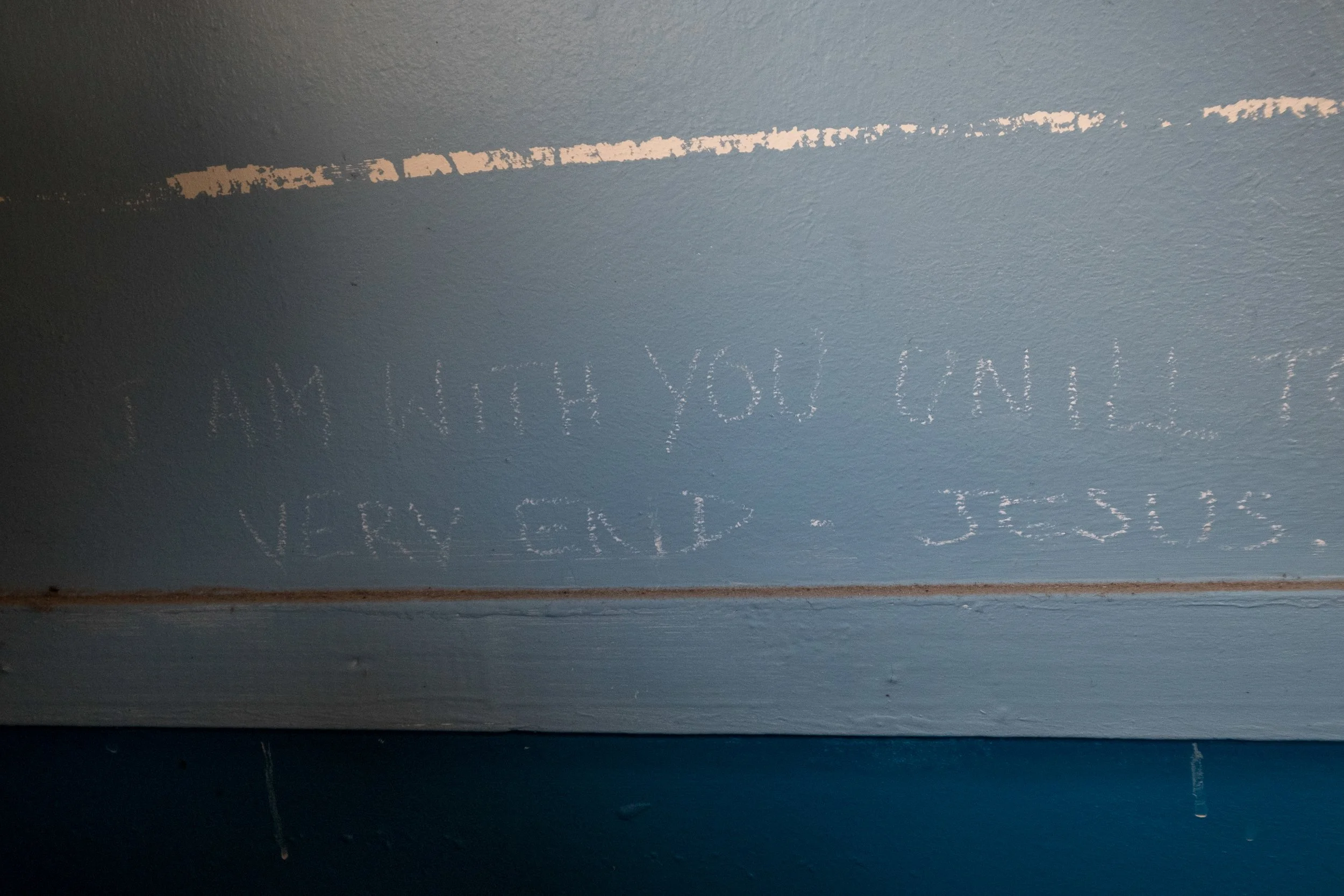

Inside, the colour palette drained away any sense of life. Dark blue bars, walls washed in blues and creams, and beds bolted to the floor. A beautiful mural of a Māori woman cradling a child broke the monotony at the end of one wing, a reminder that culture and humanity still existed somewhere in the story.

The cells themselves were claustrophobic and bare. Stainless steel toilets with no seats. Tiny basins. Textured plaster to prevent any form of self-expression.

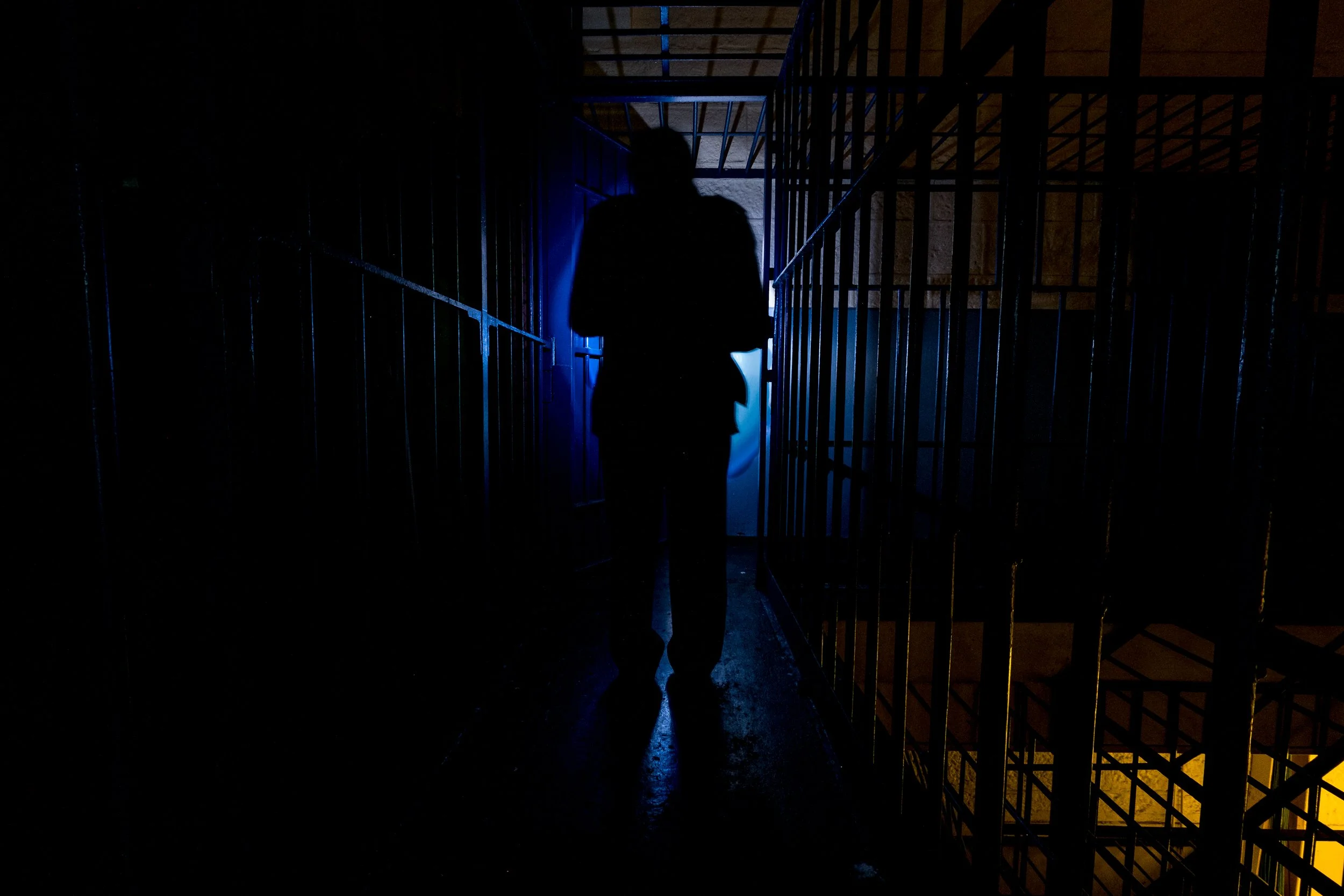

Night Visit

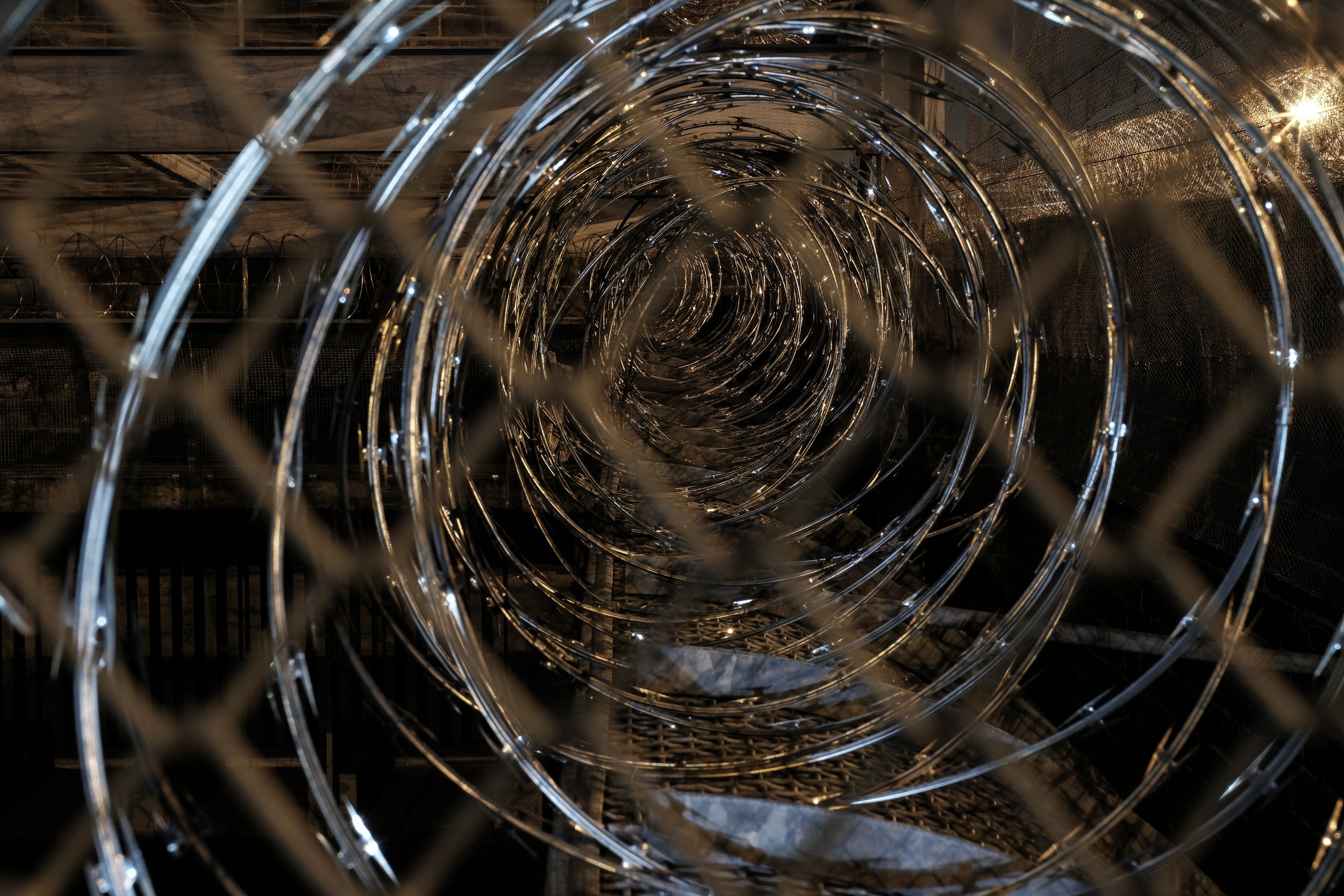

Night softened the harsh edges. The darkness wrapped the place in a strange calm, like rain drumming on a tin roof. The yards were filled with shifting shadows cast by mesh fences and coils of barbed wire. Motorway noise hummed far away, reminding me that life continued right outside these walls.

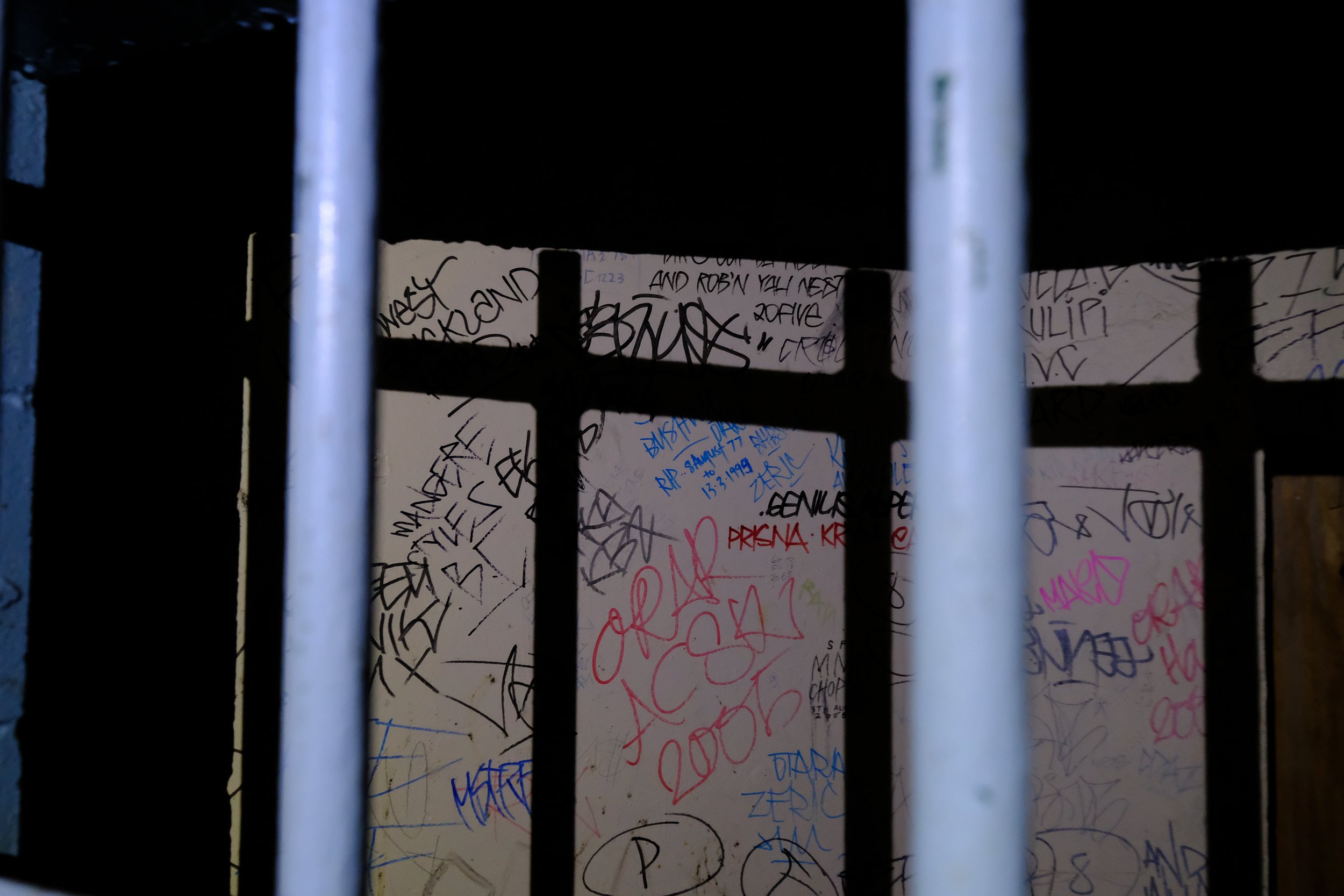

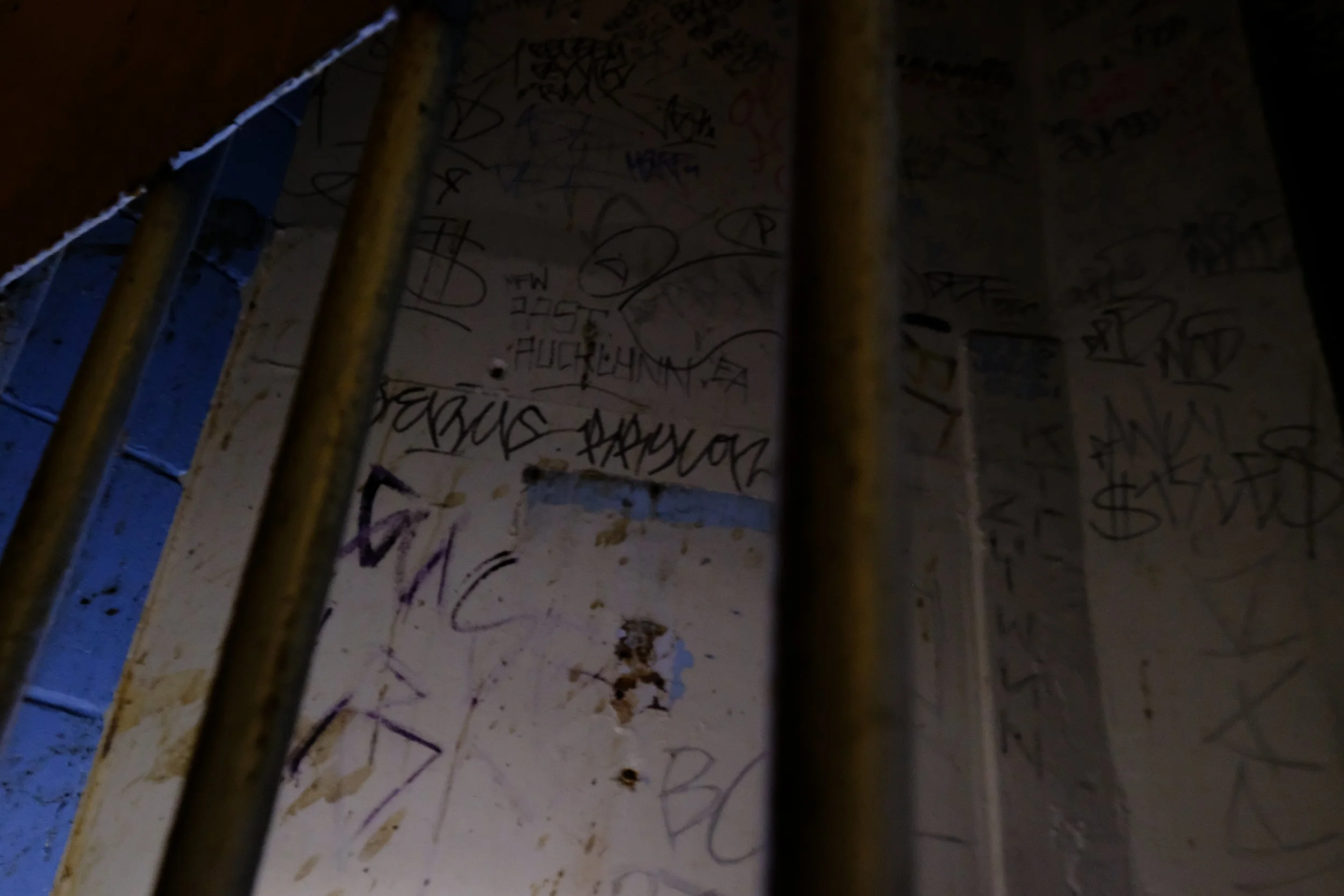

Graffiti felt different in the dark. Tags claiming gang identity seemed more like frustrated scribbles left behind by men who needed to prove something to someone.

The guards led me to the former death row cells. I closed myself inside one. Cold. Cramped. The kind of silence that presses against you. I lit tea candles and asked for the lights to be turned off. The only glow came from my torch and that weak flame fighting the darkness. I wanted to understand the psychological weight these walls held.

Some ghost lore was shared as we moved. Interesting. Creepy. Yet the real horror lay in the stories of daily life here: violence, fear, power, despair. Ghosts felt optional. Trauma was not.

Prison Art

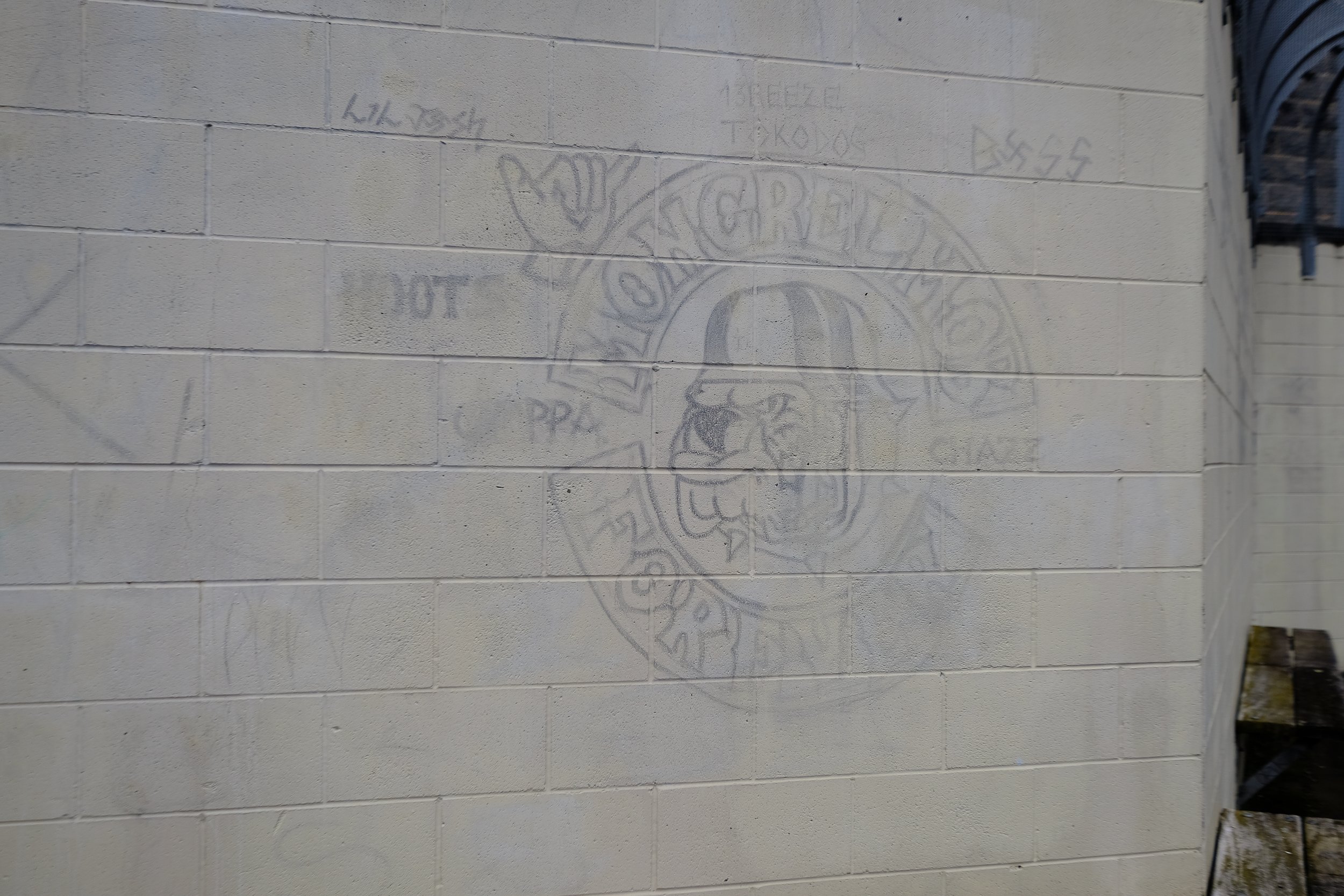

There were moments of unexpected creativity. Murals and cartoons brightened some of the internal wings and visiting areas. Lord of the Rings characters, hand-painted landscapes, names scrawled as a claim of existence. Art as escape. Art as rebellion. Gang insignia to perhaps lay claim to an area in a recreation yard.

Reflections

Walking those corridors made it clear that punishment once outweighed rehabilitation by a long distance. The leaking walls, the cold, the absence of comfort. If this place was ever meant to correct behaviour, it feels like it more often hardened those who passed through its doors.

Many men must have walked out angrier than when they walked in.

Not every story ends that way, of course. No doubt many men rebuilt their lives. Yet the design and conditions here seemed destined to crush rather than change.

This old prison is a reminder of a justice system that perhaps once tried to maintain order through fear. A reminder of policies that once prioritised containment over humanity. A reminder that behind every wall is a story we don’t always want to hear.